It’s possible to get hung up on detail and precision when writing a business plan, a bit like writing a piece of classical music. In fact, business planning is more like writing music for jazz musicians: less detail and space to improvise.

It’s possible to get hung up on detail and precision when writing a business plan, a bit like writing a piece of classical music. In fact, business planning is more like writing music for jazz musicians: less detail and space to improvise.

In this short – and hopefully not boring – video I offer a cure for what could be termed “Founders Syndrome” – a focus on the core mission and purpose that can obscure the dull but necessary tasks required to help the organisation grow.

The exciting mission and purpose need to be balanced against the dull stuff – and good planning is essential

Are you excited by your working life? Does every problem seem like a solution waiting to happen? Do you spend most of the day in a state of feverish anticipation about the next curveball that the world is going to sling at you?

If the answer is “no, not often” then you have much in common with 99.9% of people in organisations around the world: however much your organisation has a great cause, a compelling purpose, whizzy products and funky offices with great coffee on tap and a pinball machine in the basement, you have to spend a large chunk of your day doing stuff that’s – when all’s said and done – pretty boring.

In a large business the stuff that we might find a bit dull can be allocated to people who don’t find it so: that’s why we have Finance, HR, Procurement and so on. If you’re lucky, those departments will be full of people who can eat a purchase ledger for breakfast without batting an eyelid and will be happy to do so day in, day out.

It’s an end-to-end problem – and an opportunity

I was in conversation with a fellow consultant recently where she described her horrendous experience returning a sofa she had bought. You’d think this would be a straightforward exercise – these days I find it’s straightforward to return unworn or undamaged products to suppliers and get a refund – but not so. In this case the sofa had been covered with a fabric that, after a few weeks, had stretched significantly, making the whole thing look worn and unattractive.

My friend’s initial attempt to sort out a return was rebuffed but she was undeterred and sought out help from a fabric expert, who confirmed that the fabric used was too stretchy and therefore unsuitable for use as a sofa covering, and a lawyer friend who obliged her with a suitably stiff letter.

To focus your project, add a To-Not-Do list to your to-do list

There’s an exercise that’s both entertaining and useful when setting up and planning a new project or business venture: thinking of all the ways you could make it fail.

We tend to think of plans as precise specifications like compositions, but writing for jazz musicians is a better analogy

I specialise in creating robust, implementable strategies and plans for organisations going through times of change. Somewhere along the line a plan gets delivered, whether it’s me writing it or my clients, but I think there’s a bit of a misconception about the role of plans and to me it’s best explained with an analogy.

We have a tendency to think of a plan as a precise specification of what will happen, a bit like a musical composition. In western classical music – at least for last 400 years or so – it’s been written down precisely so that the musicians play exactly what the composer intended.

In this video I discuss how saying no can aid you in your business planning and your personal productivity by providing an opportunity to focus and prioritise. I also share two simple techniques to help you have more productive planning conversations.

Purpose is key, but you need vision to inform it

Many years ago, I was on one of the least fulfilling consulting projects I have ever carried out. It had all the hallmarks of success – prestige international client, great colleagues, working in London and New York – but the only problem was that the director who’d hired us didn’t seem to know what problem we were there to solve. It wasn’t all bad, as the client team were an interesting bunch: highly motivated, very hard-working… and as cynical as they come. One remark has stuck with me through the decades: referring to a member of the client organisation who was seen as making a potentially useful contribution to the project one of the team referred to him as “a bit of a visionary”. However, the way she said this – the particular tone of her voice – suggested that his contribution would be far from useful.

So, what’s the problem with visions and visionaries – and are they any use when we are increasingly concerned with an organisation’s purpose?

When I talk about vision, mission and purpose in strategy courses and workshops, I do a quick quiz as an icebreaker, using a slide with the following three people on it:

I ask people to name them and tell me which one is the odd one out. People usually guess the two chaps on the left and right – Steve Jobs and Elon Musk – but have a bit more difficulty with the central character, possibly as she wasn’t responsible for a prestige tech brand. It’s Hildegard of Bingen, the 12th Century German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary, and polymath. She’s the odd one out, not just because she is female, but because she was the only one amongst the three to have actual visions.

Now I’m not saying that this makes Hildegard more or less of a visionary than the other two – even if some people have attributed her visions to temporal lobe epilepsy or migraine – but I bring her in to the conversation to make the point that there is a bit of a problem with visions and visionaries. The fact that I have cited three high achievers who have made significant advances in their chosen fields means that “being a visionary” – my former client colleague notwithstanding – or having a vision is seen as something “out there” and exceptional; something not for normal people.

I contend that this is nonsense.

Why?

Having and articulating a vision is something we should all do, whether it’s for our companies, our neighbourhoods, our families or ourselves. And developing it is fairly straightforward: you simply complete the following sentence:

“A world where…”

“World” in this context doesn’t necessarily mean the whole world, it could be the world of your company, division, family or just you.

To give you a concrete example close to me, I work with a music education charity, World Heart Beat, whose vision includes

“a world where music, as a universal form of communication, bridges cultural, political, economic and linguistic barriers”.

What I like about this vision is that, whilst it could be some distant future world, it’s quite possible to realise it on a local scale, i.e. in the parts of London that the charity operates in – and indeed it translates this vision into the way its courses, concerts and other events are put together.

So, a vision can be both far away and present at the same time: in fact, if it’s a dream – as Martin Luther King so powerfully articulated – or a state that may seem distant when compared to the present, it’s actually more useful than one which too strongly implies a destination.

A lot of vision statements I have seen make the mistake of extending what the person or the company currently does into a more ambitious version of themselves. So a vision statement like:

“providing high quality solutions for the supply chain market”

isn’t a vision statement. Instead, envisioning

“a world where supply chains are friction-free, enabling clients to optimise their manufacturing and distribution schedules to deliver more cost-effective solutions to their customers”

would, I think, be a bit more ambitious and, moreover, emphasise the benefit of such a world.

Vision statements that include a destination are basically mission statements, perhaps most famously (if you spent too much time in your youth watching science fiction on TV) in the mission of the Starship Enterprise. A mission has some sort of objective and, like a vision, needs to be powerful to motivate the team(s) involved in delivering it. The vision may be delivered by implementing the mission but actually the most powerful visions are those that don’t define a specific destination.

The emphasis on purpose to provide a focus for the organisation might be seen as removing the need for mission and vision statements. I’d argue that the opposite is true: a definition of the organisation’s purpose – the why as Simon Sinek refers to it – is best arrived at when you have a vision to accompany it (and a mission to deliver it).

To craft a purpose statement is simple but requires deep thought and discussion to get there. A sentence with the structure:

To [contribution] so that [outcome]

is all you need but agreeing the contribution (the timeless value-adding work you do) and the outcome (the benefit for your customers) is a non-trivial conversation.

In my strategy and planning workshops I spend time on all three, spending most time on the one that’s insufficiently well-defined, as it teases out the motivators and the direction to create alignment before we get into the things that need to change and their relative priority. Vision is often the most powerful element of that conversation, as people share their real feelings about the business, what it contributes (beyond a healthy balance sheet) and how they see themselves in it.

The vision thing is still necessary and, in what appears to be an increasingly fractious world, I’d argue that we need powerful, ambitious visions more than ever.

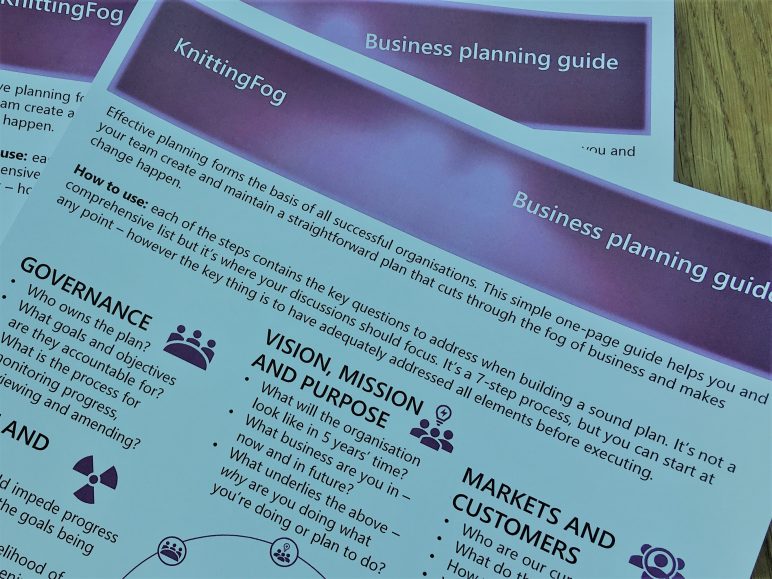

You can find out how vision fits in to the KnittingFog approach to strategy and business plan development by downloading my one-page guide.

If you’re in need of an aide memoire to help structure your business planning process I’m delighted to offer a simple one page guide.

Why one page? Well, planning can be a complex process once you start to consider all the various factors that need to be taken into consideration so it’s best to start simple.

I’ve condensed my experience of change management, strategy and planning into seven steps and the key questions you should ask at each step. These should be taken as the starting point from the key stakeholders that you need to involve.

To get the guide please follow this link.

In a sea of endless possibility, discover the power of not doing something

A while ago a business associate and I were discussing a joint venture we had planned to do. Reviewing our various activities over the coming months we decided there was no way we were going to be able to do what we’d talked about until next year, so we said a decisive “no” to doing it now.

And it felt liberating.

Modern business culture rightly encourages positivity, but the unintended consequences can make you feel overloaded. Selective use of negativity can have a positive effect. Here’s how…

Early on in my consulting career I worked with a colleague who had a background in sales training. My relationship with our client was not as good as it could be, and she offered me perhaps the simplest and best consulting advice I’ve ever had. I’d come from a technical and analytic background where options tended to be carefully weighed against agreed criteria and recommendations made. As a result, my answers to client questions in the early stage of their transformation project were of the “it depends” variety. My colleague realised this wasn’t helping them get started on a big change, so she sat me down and said

“When a client asks you if we can do something, what’s your answer?”

Before I could come out with “it depends” she produced a sheet of A4 paper with one word on it in large font:

“The answer is always yes” she said “even if you can think of a thousand reasons why it’s not possible. The client wants help. They want to know what’s possible, so entertain the possibility before dismissing it or even trying to evaluate it.”

It’s a classic sales technique, of course: agree that you can provide what the customer wants even if you can’t figure out how to provide it. It works equally well in change and transformation projects, where people need to try out a new idea to see if it could work. As a consultant part of your role is to help envision this new world not dismiss it out of hand.

Saying Yes to everything is a life and work strategy that means you embrace possibilities and adopt a more positive mindset. But it has its downsides: if everything is possible, then what do you do?

I encounter this all the time with clients I work with, particularly smaller non-profit organisations who invariably have resource or budget challenges that mean that the list of things they would like to do starts to seem un-doable. My lesson from many years ago means that I don’t tell people what they can’t do but I do work through a process that helps them focus on what must be done now, what could be done given budget (and a plan to get it) and what doesn’t really need to be done.

I find that once people say no – or not-yet – to a few things on the seemingly impossible to-do list, the forward plan becomes more manageable.

Any change initiative or ambitious plan will usually flush out the “nay-sayers” in the organisation, those people for whom every silver lining has a cloud, and the fashion for positive thinking means that their views can often get discounted. I have had a lot of experience with IT departments over the years and that’s where a lot of perceived negativity comes from, usually in the form of too-long development timescales or too-high budgets. In these cases, there is a disconnect between the ambition stated by the person who had the idea and the nay-sayers view of reality. I think change efforts need to have nay-sayers on the team to temper any over-optimism but also, when they do come on board, either through compromise or coming round to the argument, they become rock-solid advocates for change.

A couple of questions to see if you’re embracing the power of Yes and No:

There’s no hard and fast answer to these questions, but addressing them means your change plans are much more likely to succeed.

* If you can remember this then, like me, you spent too much of your childhood watching TV or you and I have similar taste in music